Activity lifecycle and state

What is activity lifecycle ?

The activity lifecycle is the set of states an activity can be in during its entire lifetime, from the time it's created to when it's destroyed and the system reclaims its resources. As the user interacts with your app and other apps on the device, activities move into different states.

For example:

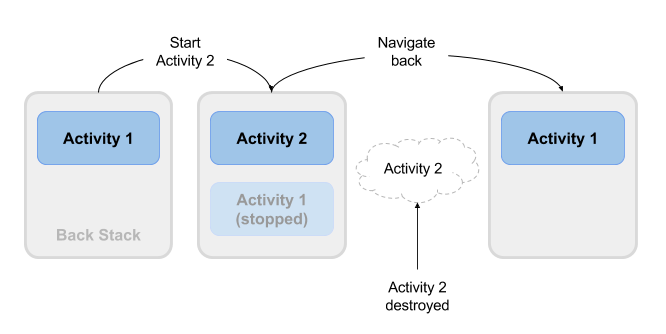

When you start an app, the app's main activity ("Activity 1" in the figure below) is started, comes to the foreground, and receives the user focus.

When you start a second activity ("Activity 2" in the figure below), a new activity is created and started, and the main activity is stopped.

When you're done with the Activity 2 and navigate back, Activity 1 resumes. Activity 2 stops and is no longer needed.

If the user doesn't resume Activity 2, the system eventually destroys it.

Activity states and lifecycle callback methods

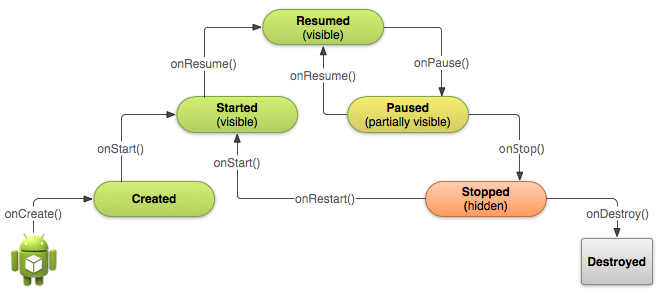

When an Activity transitions into and out of the different lifecycle states as it runs, the Android system calls several lifecycle callback methods at each stage. All of the callback methods are hooks that you can override in each of your Activity classes to define how that Activity behaves when the user leaves and re-enters the Activity. Keep in mind that the lifecycle states (and callbacks) are per Activity, not per app, and you may implement different behavior at different points in the lifecycle of each Activity.

This figure shows each of the Activity states and the callback methods that occur as the Activity transitions between different states:

Depending on the complexity of your Activity, you probably don't need to implement all the lifecycle callback methods in an Activity. However, it's important that you understand each one and implement those that ensure your app behaves the way users expect. Managing the lifecycle of an Activity by implementing callback methods is crucial to developing a strong and flexible app.

Activity created: the onCreate() method

Your Activity enters into the created state when it is started for the first time. When an Activity is first created, the system calls the onCreate() method to initialize that Activity. For example, when the user taps your app icon from the Home screen to start that app, the system calls the onCreate() method for the Activity in your app that you've declared to be the "launcher" or "main" Activity. In this case the main Activity onCreate() method is analogous to the main() method in other programs.

Similarly, if your app starts another Activity with an Intent (either explicit or implicit), the system matches your Intent request with an Activity and calls onCreate() for that new Activity.

The onCreate() method is the only required callback you must implement in your Activity class. In your onCreate() method you perform basic app startup logic that should happen only once, such as setting up the user interface, assigning class-scope variables, or setting up background tasks.

Created is a transient state; the Activity remains in the created state only as long as it takes to run onCreate(), and then the Activity moves to the started state.

Activity started: the onStart() method

After your Activity is initialized with onCreate(), the system calls the onStart() method, and the Activity is in the started state. The onStart() method is also called if a stopped Activity returns to the foreground, such as when the user clicks the Back button or the Up button to navigate to the previous screen. While onCreate() is called only once when the Activity is created, the onStart() method may be called many times during the lifecycle of the Activity as the user navigates around your app.

When an Activity is in the started state and visible on the screen, the user cannot interact with it until onResume() is called, the Activity is running, and the Activity is in the foreground.

Typically you implement onStart() in your Activity as a counterpart to the onStop() method. For example, if you release hardware resources (such as GPS or sensors) when the Activity is stopped, you can re-register those resources in the onStart() method.

Started, like created, is a transient state. After starting, the Activity moves into the resumed (running) state.

Activity resumed/running: the onResume() method

Your Activity is in the resumed state when it is initialized, visible on screen, and ready to use. The resumed state is often called the running state, because it is in this state that the user is actually interacting with your app.

The first time the Activity is started the system calls the onResume() method just after onStart(). The onResume() method may also be called multiple times, each time the app comes back from the paused state.

As with the onStart() and onStop() methods, which are implemented in pairs, you typically only implement onResume() as a counterpart to onPause(). For example, if in the onPause() method you halt any animations, you would start those animations again in onResume().

The Activity remains in the resumed state as long as the Activity is in the foreground and the user is interacting with it. From the resumed state the Activity can move into the paused state.

Activity paused: the onPause() method

The paused state can occur in several situations:

The

Activityis going into the background, but has not yet been fully stopped. This is the first indication that the user is leaving yourActivity.The

Activityis only partially visible on the screen, because a dialog or other transparentActivityis overlaid on top of it.In multi-window or split screen mode (API 24), the

Activityis displayed on the screen, but some otherActivityhas the user focus.

The system calls the onPause() method when the Activity moves into the paused state. Because the onPause() method is the first indication you get that the user may be leaving the Activity, you can use onPause() to stop animation or video playback, release any hardware-intensive resources, or commit unsaved Activity changes (such as a draft email).

The onPause() method should execute quickly. Don't use onPause() for CPU-intensive operations such as writing persistent data to a database. The app may still be visible on screen as it passes through the paused state, and any delays in executing onPause() can slow the user's transition to the next Activity. Implement any heavy-load operations when the app is in the stopped state instead.

Note that in multi-window mode (API 24), your paused Activity may still fully visible on the screen. In this case you do not want to pause animations or video playback as you would for a partially visible Activity. You can use the inMultiWindowMode() method in the Activity class to test whether your app is running in multi-window mode.

Your Activity can move from the paused state into the resumed state (if the user returns to the Activity) or to the stopped state (if the user leaves the Activity altogether).

Activity stopped: the onStop() method

An Activity is in the stopped state when it's no longer visible on the screen. This is usually because the user started another activity or returned to the home screen. The Android system retains the activity instance in the back stack, and if the user returns to the activity, the system restarts it. If resources are low, the system might kill a stopped activity altogether.

The system calls the onStop() method when the activity stops. Implement the onStop() method to save persistent data and release resources that you didn't already release in onPause(), including operations that may have been too heavyweight for onPause().

Activity destroyed: the onDestroy() method

When your Activity is destroyed it is shut down completely, and the Activity instance is reclaimed by the system. This can happen in several cases:

You call

finish()in yourActivityto manually shut it down.The user navigates back to the previous

Activity.The device is in a low memory situation where the system reclaims any stopped

Activityto free more resources.A device configuration change occurs. You learn more about configuration changes later in this chapter.

Use onDestroy() to fully clean up after your Activity so that no component (such as a thread) is running after the Activity is destroyed.

Note that there are situations where the system will simply kill the hosting process for the Activity without calling this method (or any others), so you should not rely on onDestroy() to save any required data or Activity state. Use onPause() or onStop() instead.

Activity restarted: the onRestart() method

The restarted state is a transient state that only occurs if a stopped Activity is started again. In this case the onRestart() method is called between onStop() and onStart(). If you have resources that need to be stopped or started you typically implement that behavior in onStop() or onStart() rather than onRestart().

Configuration changes and Activity state

Earlier in the section on onDestroy() you learned that your Activity may be destroyed when the user navigates back, or when your code executes the finish() method, or when the system needs to free resources. Another way an Activity can be destroyed is when the device undergoes a configuration change.

Configuration changes occur on the device, in runtime, and invalidate the current layout or other resources in your Activity. The most common form of a configuration change is when the device is rotated. When the device rotates from portrait to landscape, or from landscape to portrait, the layout for your app needs to change. The system recreates the Activity to help that Activity adapt to the new configuration by loading alternative resources (such as a landscape-specific layout).

Other configuration changes can include a change in locale (the user chooses a different system language), or the user enters multi-window mode (Android 7). In multi-window mode, if you have configured your app to be resizeable, Android recreates the Activity to use a layout definition for the new, smaller size.

When a configuration change occurs, the Android system shuts down your activity, calling onPause(), onStop(), and onDestroy(). Then the system restarts the activity from the beginning, calling onCreate(), onStart(), and onResume().

Activity instance state

When an Activity is destroyed and recreated, there are implications for the runtime state of that Activity. When an Activity is paused or stopped, the state of the Activity is retained because that Activity is still held in memory. When an Activity is recreated, the state of the Activity and any user progress in that Activity is lost, with these exceptions:

Some

Activitystate information is automatically saved by default. The state ofViewelements in your layout with a unique ID (as defined by theandroid:idattribute in the layout) are saved and restored when anActivityis recreated. In this case, the user-entered values inEditTextelements are usually retained when theActivityis recreated.The

Intentthat was used to start theActivity, and the information stored in the data or extras for thatIntent, remains available to thatActivitywhen it is recreated.

The Activity state is stored as a set of key/value pairs in a Bundle object called the Activity instance state . The system saves default state information to instance state Bundle just before the Activity is stopped, and passes that Bundle to the new Activity instance to restore.

You can add your own instance data to the instance state Bundle by overriding the onSaveInstanceState() callback. The state Bundle is passed to the onCreate() method, so you can restore that instance state data when your Activity is created. There is also a corresponding onRestoreInstanceState() callback you can use to restore the state data.

Test that your Activity behaves correctly when the user rotates the device, because device rotation is a common use case. Implement instance state if you need to.

Note: The Activity instance state is particular to a specific instance of an Activity, running in a single task. If the user force-quits the app or reboots the device, or if the Android system shuts down the app process to preserve memory, the Activity instance state is lost. To keep state changes across app instances and device reboots, you need to write that data to shared preferences. You learn more about shared preferences in another chapter.

Saving Activity instance state

To save information to the instance state Bundle, use the onSaveInstanceState() callback. This is not a lifecycle callback method, but it is called when the user is leaving your Activity (sometime before the onStop() method).

The onSaveInstanceState() method is passed a Bundle object (a collection of key/value pairs) when it is called. This is the instance state Bundle to which you will add your own Activity state information.

You learned about Bundle in a previous chapter when you added keys and values to the Intent extras. Add information to the instance state Bundle in the same way, with keys you define and the various "put" methods defined in the Bundle class:

Don't forget to call through to the superclass, to make sure the state of the View hierarchy is also saved to the Bundle.

Restoring Activity instance state

Once you've saved the Activity instance state, you also need to restore it when the Activity is recreated. You can do this one of two places:

The

onCreate()callback method, which is called with the instance stateBundlewhen theActivityis created.The

onRestoreInstanceState()callback, which is called afteronStart()after theActivityis created.

Most of the time the better place to restore the Activity state is in onCreate(), to ensure that your UI, including the state, is available as soon as possible.

To restore the saved instances state in onCreate(), test for the existence of a state Bundle before you try to get data out of it. When your Activity is started for the first time there will be no state and the Bundle will be null.

Last updated